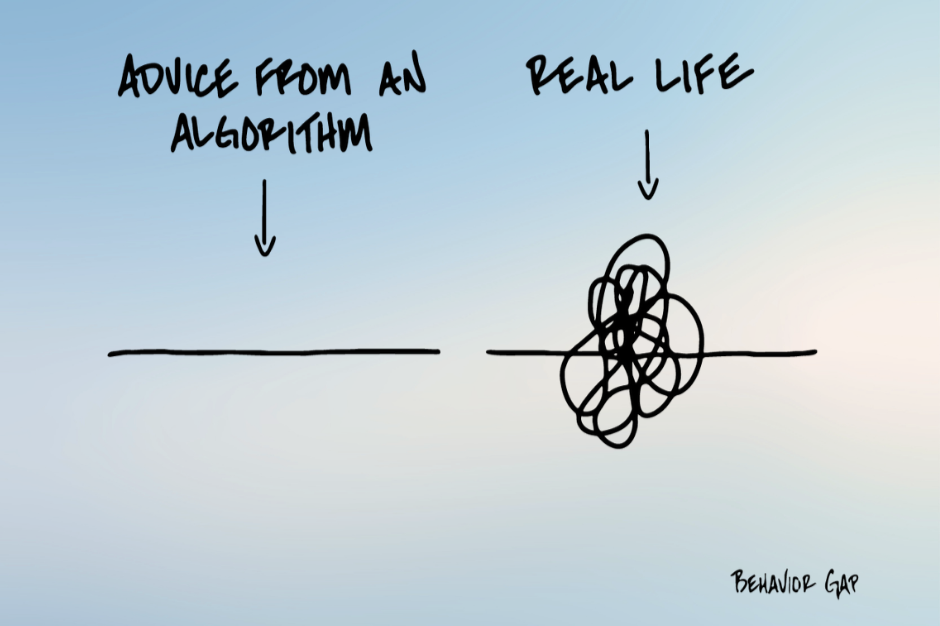

You know what real life looks like? Messy. But you wouldn't know it from most financial plans – not algorithmic ones, anyway.

Most advice out there comes as a straight line. A tidy formula. Clean inputs, clean outputs. Do X, get Y! Save this percentage, retire at that age. Follow these steps, achieve this outcome.

But real life is messier. It's a chaotic tangle of loops and knots and unexpected detours.

And here's the thing about that mess—it's not a bug. It's not a sign you're doing it wrong. It's not evidence that you're bad with money or that you lack discipline. The mess is the point. The mess is what makes us human.

The Seduction of the Straight Line

There's something deeply appealing about algorithmic advice. It’s so clean. Plug in your numbers, and out comes a plan: no ambiguity, no second-guessing. Just follow the formula.

When you're overwhelmed by financial decisions, a straight line feels like relief. Someone—or something—finally has the answer. “Just tell me what to do, and I'll do it!”

Everything’s mapped out. It’s paint by numbers, just like when you were a kid.

But here's what the algorithm doesn't know: it doesn't know that your mother just got diagnosed with cancer and you're trying to figure out if you can afford to take unpaid leave. It doesn't know that your child is struggling in school and needs a tutor you hadn't budgeted for. It doesn't know that you just got an unexpected bonus and you're torn between paying down debt, investing, or finally taking that trip you've been postponing for five years.

The algorithm doesn't know that you're human, and life changes.

Why Math Isn't Enough

Don’t be mistaken - the maths matters. Of course it does! Compound interest is real. Time value of money is real. The difference between a 6% return and an 8% return over thirty years is very real.

But when we reduce money to maths alone, we forget what it feels like to make decisions when you're scared. Or uncertain. Or grieving. Or excited. Or exhausted. Or newly in love. Or watching your industry collapse. Or getting a second chance you never expected.

Financial decisions aren't made in a vacuum. They're made in the tangled middle of actual lives.

That's why human financial advice still matters. Not because humans are better at maths than machines—we're definitely not. But because good advisors know that the maths is just the beginning. The real work is helping people navigate the gap between what the spreadsheet says they should do and what feels possible in their actual circumstances.

Algorithms Optimise, Humans Navigate

Here's what I've learned after years of working with people and their money: algorithms optimise for efficiency. Humans navigate complexity.

An algorithm can tell you the mathematically optimal move. But it can't tell you whether that move is worth the fight it'll cause with your spouse. It can't weigh the emotional cost of saying no to your child’s sports travel team against the financial benefit of staying on track. It can't factor in the value of sleeping soundly at night, even if that means choosing a less "optimal" investment.

There's a reason Japanese retirement homes started removing robots and bringing back human caregivers.1 The robots were more efficient. They didn't get tired. They didn't call in sick. They could lift residents without risking back injuries. But the residents wanted the human touch. They wanted someone who could sense when they needed comfort, not just assistance. Someone who could respond to mood, not just medication schedules.

The same principle applies to money. The algorithm gives you the straight line. The human advisor helps you draw your actual path through the tangled mess.

And sometimes the best financial decision isn't the one that maximizes your net worth. Sometimes it's the one that lets you live with yourself. Sometimes it's the one that honours your values, even when it costs you. Sometimes it's the one that acknowledges you're not just a rational economic agent making optimal choices—you're a person trying to build a life that matters.

You Don't Know Where You Sit on the Curve

Late last year, I wrote about how no one actually knows where they sit on the curve of life's probabilities.2 The algorithm assumes average. But you're not living an average life—you're living your specific life, with your specific luck (good and bad) in any given year. My claims year proved that perfectly.

Some years, you sail through with nothing but routine expenses. The algorithm would call that "optimal."

Other years, everything hits at once. Three family emergencies, a job loss, a health scare, and a busted gearbox. The algorithm would call that "suboptimal" or "poor planning."

Yet, both years are just… life. You didn't do anything wrong in the hard year. You didn't do anything especially right in the easy year. You just lived as normal, where probability meets reality and the straight line becomes a scribble.

The Question Worth Asking

So here's what I want you to ask someone you care about today: What did your budget not account for this past year?

Budgets are great. I believe in them. But they're not magic. Real life always sneaks something in. The car repair. The friend's wedding at the other end of the country. The opportunity you couldn't pass up. The emergency that wasn't really an emergency but felt like one at the time.

Those deviations from the plan? They're not failures. They're data. They're information about what your life actually requires, not what the algorithm thinks it should require.

The straight line is beautiful. But the tangled mess is real. And real is where we have to learn to make good decisions.

Why We Still Seek Human Advice

Here's the deeper truth about why people still seek human financial advice in an age of robo-advisors and AI-powered planning tools: life is dynamic, and our responses need to be too.

A good financial plan isn't static. It breathes. It adapts. It changes when your circumstances change, when your values shift, when unexpected opportunities arise or unwanted challenges appear.

The algorithm updates when you feed it new numbers. The human advisor updates when they see the worry in your eyes, hear the excitement in your voice, sense the hesitation you can't quite articulate. They adjust not just to what has changed, but to how you've changed.

Because here's what the tangled mess really represents: not chaos, but adaptation. Not failure, but responsiveness. Not a deviation from the plan, but evidence that you're paying attention to your actual life and adjusting accordingly.

The straight line assumes the future will be like the past. The tangled line knows better. It knows that life zigs when you expect it to zag. It knows that the best plan is one that can bend without breaking, that can accommodate both disaster and delight, that can hold space for the full complexity of being human.

That's not a bug in the system. That's the whole point of having a life worth planning for.

Nick Stewart

(Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Huirapa, Ngāti Māmoe, Ngāti Waitaha)

Financial Adviser and CEO at Stewart Group

Stewart Group is a Hawke's Bay and Wellington based CEFEX & BCorp certified financial planning and advisory firm providing personal fiduciary services, Wealth Management, Risk Insurance & KiwiSaver scheme solutions.

The information provided, or any opinions expressed in this article, are of a general nature only and should not be construed or relied on as a recommendation to invest in a financial product or class of financial products. You should seek financial advice specific to your circumstances from a Financial Adviser before making any financial decisions. A disclosure statement can be obtained free of charge by calling 0800 878 961 or visit our website, www.stewartgroup.co.nz

Article no. 440

References

James Wright's research on Japanese eldercare facilities found that care workers often rejected robots like the "Hug" lifting device, preferring to care with their own hands and finding it more respectful to residents. See: Wright, James. Robots Won't Save Japan: An Ethnography of Eldercare Automation (Cornell University Press, 2023); and MIT Technology Review's coverage of robot implementation challenges in Japanese care homes (January 2023). ↩

"Why Self-Insurance Rarely Works," Stewart Group, December 5, 2024 ↩