In late 2023, New Zealanders voted decisively for change. After six years of Labour government under Jacinda Ardern and Chris Hipkins, the country was exhausted. The NZX had become one of the worst‑performing stock markets in the developed world [1]. Trust in core institutions, from the police to the healthcare system, had cratered [2]. Real economic growth was negative [3]. The cost of living was crushing ordinary families, while housing remained stubbornly unaffordable.

The coalition government swept to power on a mandate to reverse this decline. But two years later, that mandate has been squandered through timidity and a fatal misreading of the moment.

It's tempting to view this government's approach through the lens of John Key and Bill English's post‑GFC strategy. Between 2008 and 2017, that duo carefully managed spending cuts while allowing growth to flourish organically [4]. They made incremental reforms, maintained fiscal discipline, and let the private sector drive recovery. It worked brilliantly. Unemployment fell, growth returned, and National won three consecutive elections.

But 2026 is not 2010, and the global playing field has fundamentally changed. Interest rates have surged after over a decade of easy money [5]. New Zealand's underlying productivity crisis can no longer be ignored [6].

This government has tried to apply the Key‑English playbook to a radically different situation. Ministers speak reassuringly of “green shoots”, yet the economy contracted 0.9% in Q2 2025, then grew just 1.1% in Q3, a volatile pattern that speaks to underlying fragility rather than sustained recovery [7]. Real GDP per capita continues falling [8].

The retail sector tells the story most viscerally. Boxing Day sales slumped 12.4%, consumers spent just $51.2 million on non‑food retail, down from $58.5 million the previous year [9]. As Simplicity chief economist Shamubeel Eaqub observed, “For a lot of businesses this should be their saving grace” [10].

January 2026 brought only marginal relief: core retail spending lifted a mere 0.6% compared to the same month last year, with weather events depressing regional performance and retailers “just treading water as the economy moves sideways, rather than forwards,” according to Retail NZ CEO Carolyn Young [11]. In the meantime, retail business liquidations surged 34% year‑on‑year [12].

Consider ACT leader David Seymour's State of the Nation speech on Sunday, where he diagnosed the core problem with brutal clarity. “People work their guts out only to find that they're further behind,” he said, noting young New Zealanders simply “can't make the numbers add up” when looking at student loans, wages, taxes, and housing costs. He called emigration a “flashing light on the dashboard” and observed that previous generations worked hard “because hard work was a rewarding strategy. That deal feels broken.” He admitted the government is “on track to post a small surplus by 2030, but after that, our ageing population will put us back in the red for more decades of deficit spending.” Yet his proposed solution, reducing the number of ministers to 20 and departments to 30, only epitomises the incrementalism that has defined this government. When your coalition partner polling at 7.6% is calling for bolder action than you are, you've misread the moment [13].

With the election now confirmed for 7 November 2026, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon’s party has a narrow lead in recent polls, but the fundamentals are troubling. The latest Roy Morgan poll has National at 34.5% compared to Labour's 30.5%, with the coalition government on 52% versus the opposition's 44% [14]. Yet 51.5% of voters say New Zealand is “heading in the wrong direction” [15].

The Argentina Mirror

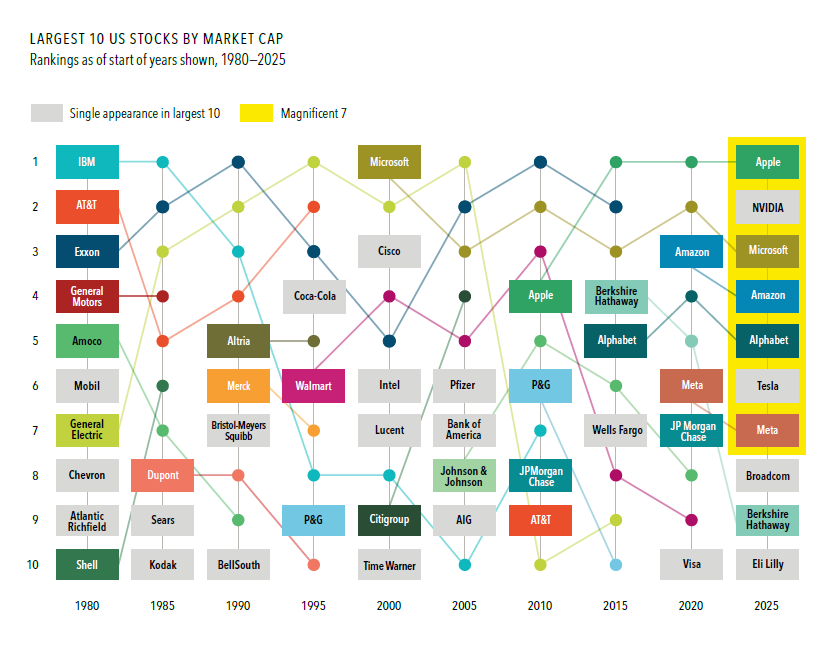

In 1913, Argentina's per capita income exceeded Germany, France, Sweden, Italy, and Spain [16]. Like New Zealand, it was a resource‑rich agricultural powerhouse built on classical liberal foundations. Both countries ranked among the world's wealthiest in the first half of the 20th century [17].

Argentina's fall was dramatic. Decades of Peronist corporatism culminated in the crisis that brought Javier Milei to power. By December 2023, Argentina faced 211% annual inflation, 42% poverty, a 15% quasi‑fiscal deficit, and an economy in free fall [18].

Milei cut the budget by 30% and balanced it by his second month in the job [18]. He implemented 1,246 deregulations through August 2025 [18]. He abolished 10 ministries and fired more than 53,000 public employees [18]. Annual inflation fell from 211% to around 32% by January 2026 [18–21]. GDP grew 6.3% and investment surged 32% in the second quarter of 2025 [18]. More than 11 million people have been pulled out of poverty [18].

The results are transformative. After Milei eliminated rent controls, rental housing supply tripled and real prices fell 30% [18]. When he deregulated agricultural markets, vaccine costs for livestock producers dropped by two‑thirds [18]. Home appliance prices fell 35% after eliminating import‑licensing schemes [18].

There are real victories here. They’re 28‑year‑old Franco signing a 30‑year mortgage, “unthinkable only a couple of years ago” [18]. They’re freelancer Cecilia finally able to focus on work instead of navigating convoluted tax laws [18]. They’re farmer Pedro Gassiebayle reinvesting in his business and thinking about efficiency for the first time [18].

To be sure, Argentina's transformation faces headwinds. Monthly inflation ticked up to 2.9% in January 2026 in the fifth consecutive monthly increase, and questions have emerged about the government's statistical methodology [19–21]. The path remains narrow and fraught. But even with a few snags, the direction is unmistakable: from complete collapse toward functioning markets.

New Zealand's Drift

Compare that to New Zealand. Two years after a change in government, there's been no meaningful regulatory reform despite endless consultation. Government spending has barely been constrained [22]. Infrastructure delivery remains slow and over‑budget [23]. Housing consents have fallen [24]. The promised Fast‑track Approvals Bill has been watered down. RMA reform has been incremental when transformation was needed.

Most damningly, the fundamental drivers of our decline remain unaddressed. We still can't build houses efficiently. We still can't deliver infrastructure on time or budget. Our planning system still makes simple projects take years to consent. Meanwhile, retailers close their doors while politicians tout those elusive green shoots.

The Key‑English approach worked because the GFC was primarily a demand shock. New Zealand's current malaise is structural.

We have a productivity crisis decades in the making [25]. We have infrastructure crumbling from underinvestment [26]. We have planning and regulatory systems that strangle growth.

As Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises told Argentines in 1959: “Economic recovery does not come from a miracle; it comes from the adoption of sound economic policies” [18].

The Electoral Reckoning

With nine months until the election, this government faces an uncomfortable reckoning. Voters were promised change and received continuity. They were told to trust the process while their living standards declined. Now they're being asked to believe in green shoots while retail spending barely budges and liquidations surge.

The opposition will hammer a simple message: You had your chance and you wasted it. And they'll be right. This government has fundamentally misread the moment. It applied a playbook designed for managing cyclical downturns to a structural crisis requiring transformation.

What makes Argentina's transformation particularly instructive is that Milei turned the mainstreaming of libertarian thought into political victory [18]. He became the first political leader in 80 years to propose that the whole corporatist state had to be torn down and replaced with limited government [18]. New Zealand faces no such ideological battle. We already have strong institutions, low corruption, an independent central bank, and largely functional markets. We don't need revolution; we need our government to use the mandate voters gave them.

The tragedy is that we could reform from strength if our leaders found the courage. Instead, we're drifting toward the point where only painful corrections remain viable. Postponing necessary reforms doesn't achieve stability. It ensures that, when reform finally comes, it's painful and disruptive.

Two years ago, voters gave this government a mandate for change. Nine months from an election, with retail sales barely growing and businesses liquidating at record rates, they're learning that careful management of decline is still decline. As Milei declared to Argentines: “Either we persist on the path of decadence, or we dare to travel the path of freedom” [18].

New Zealand faces the same choice. Two years ago, voters chose change but received decadence, polite, incremental, delivered with press releases about green shoots while retailers close their doors.

Argentina's history suggests we're running out of time to change course. The voters will render their verdict on November 7.

Nick Stewart

(Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Huirapa, Ngāti Māmoe, Ngāti Waitaha)

Financial Adviser and CEO at Stewart Group

Stewart Group is a Hawke's Bay and Wellington based CEFEX & BCorp certified financial planning and advisory firm providing personal fiduciary services, Wealth Management, Risk Insurance & KiwiSaver scheme solutions.

The information provided, or any opinions expressed in this article, are of a general nature only and should not be construed or relied on as a recommendation to invest in a financial product or class of financial products. You should seek financial advice specific to your circumstances from a Financial Adviser before making any financial decisions. A disclosure statement can be obtained free of charge by calling 0800 878 961 or visit our website, www.stewartgroup.co.nz

Article no. 445

References

1. NZX. Market performance data, 2020–2023.

2. Statistics New Zealand. New Zealand General Social Survey: Trust in public institutions, 2018–2023.

3. Statistics New Zealand. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) data, 2022–2025.

4. New Zealand Treasury. Fiscal consolidation analysis, 2008–2017.

5. Reserve Bank of New Zealand. Official Cash Rate (OCR) data, 2021–2023.

6. OECD. Productivity statistics for New Zealand.

7. Statistics New Zealand. Quarterly GDP data, Q2–Q3 2025.

8. Statistics New Zealand. Real GDP per capita data, 2024–2025.

9. Worldline NZ. Retail spending data and Boxing Day sales figures, December 2025.

10. RNZ. “Tough December for retailers, as Boxing Day sales slump 12.4 percent.” 13 January 2026.

11. Inside Retail NZ / Ragtrader. Retail sector reports, January 2026.

12. Centrix. Retail business liquidations data, reported February 2026.

13. RNZ / Reid Research. Polling data on ACT Party support, January 2026.

14. Roy Morgan. New Zealand voting intention poll, January 2026.

15. Roy Morgan. Government confidence rating, January 2026.

16. Maddison Project Database. Historical GDP per capita comparisons, 1913.

17. Maddison Project Database. Long‑term international income comparisons, early 20th century.

18. Vásquez, Ian, and Marcos Falcone. “Liberty Versus Power in Milei’s Argentina.” Cato Institute – Free Society, Fall 2025.

19. ABC News. Argentina inflation reporting, February 2026.

20. Fortune. Argentina inflation and economic reform coverage, February 2026.

21. Washington Times. Argentina inflation and fiscal policy reporting, February 2026.

22. New Zealand Treasury. Budget documents, 2024–2026.

23. Infrastructure Commission Te Waihanga. Project delivery and cost‑overrun reports.

24. Statistics New Zealand. Building consents data, 2024–2025.

25. New Zealand Productivity Commission. Long‑term productivity analysis.

26. Infrastructure Commission Te Waihanga. Infrastructure deficit assessments.