With Waitangi Day upon us, it’s the perfect opportunity to reflect on what makes us unique. We're one of few nations built on a founding document promising partnership: the Treaty has been imperfectly honoured, fiercely contested, never abandoned… and the journey has taught us something valuable about moving forward without forgetting the past.

There's a story from Ngāi Tahu history that captures this lesson. It involves a sacred dogskin cloak, a violation of tapu, and a cost compounded beyond anyone's imagination.

Arowhenua Marae - Photo by Nick Stewart

The Cost of Feuds

Around 1826, while Chief Te Maiharanui was away, a woman from Waikākahi wore the kurīawarua – the Chief's sacred dogskin cloak. This act sparked the kai huānga feud: years of fighting between kin across Banks Peninsula, where the final insult to the enemy after battle was to consume them (kai huānga meaning ‘to eat a relative’, as the fighting was between hapū).[1]

This internal warfare weakened Ngāi Tahu at a crucial moment in time. Te Rauparaha of Ngāti Toa then swept down from Kapiti Coast with muskets. He found an iwi divided. The feud ended when the external threat loomed, but the damage had been done: the siege of Kaiapoi and the fall of Ōnawe found Ngāi Tahu already vulnerable because of the previous fighting.

The cloak was never worth what it ultimately cost.

The Next Fight: Te Kerēme

Ngāi Tahu learned from this. When the land was taken – eight million hectares purchased by the Crown for £2,000 through Kemp's Deed in 1848 – Ngāi Tahu made its first claim against the Crown in 1849, just one year after the deed was signed.[2]

For 149 years, generation after generation carried the fight forward. This became known as Te Kerēme (The Claim).

Above the Arowhenua Marae in Temuka, where tribal gatherings have been held for over a century, hangs the name Te Hapa o Niu Tireni: "The Broken Promises of New Zealand."[3] That name captures the weight of grievance the iwi carried, which were many and justified.

The Crown had promised reserves for Ngai Tahu of approximately ten percent of the land sold, along with schools and hospitals. None materialised.

Access to mahinga kai – traditional food gathering places – was lost.

Sacred sites and urupā were alienated.

By the early 1900s, fewer than 2,000 Ngāi Tahu remained alive in their own land, deprived of virtually everything required to survive beyond subsistence level.

The fight for justice took many forms. In 1877, the prophet Hipa Te Maiharoa led over 100 followers to Te Ao Mārama in the upper Waitaki – land he maintained had never been legitimately sold under Kemp's Deed. For two years they cultivated kai and taught tikanga, a peaceful assertion of rights that had been ignored.[4] When the armed constabulary came in 1879, Te Maiharoa chose not to shed blood. They left peacefully. Though he died before any resolution, his example of principled, persistent resistance without self-destruction gave strength to the generations who continued the fight.

The struggle continued through courts, commissions, and countless petitions. When Ngāi Tahu first took Te Kerēme to court in 1868, the government passed laws to prevent the courts from hearing it. A Commission of Inquiry a decade later had its funding halted by the Crown mid-investigation. In 1887, Royal Commissioner Judge MacKay acknowledged only a "substantial endowment" of land would begin to right so many years of neglect. By 1991, at least a dozen different commissions, inquiries, courts and tribunals had repeatedly established the veracity and justice of Te Kerēme.

Fast forward to 1998. Ngāi Tahu became the first iwi to settle with the Crown under the modern Treaty settlement process. The settlement was cents on the dollar – everyone knew it. The breach had been egregious, the losses enormous. By any measure, they deserved more.

But Ngāi Tahu took the deal anyway. Full and final. As Tā Mark Solomon reflected: "The Crown reckoned full redress was worth $12 to $15 billion. Our advisers thought closer to $20 billion. We settled for $170 million — a lot less, but it allowed Ngāi Tahu to move forward, to rebuild."[5]

The Rule of 72: Investing in the future

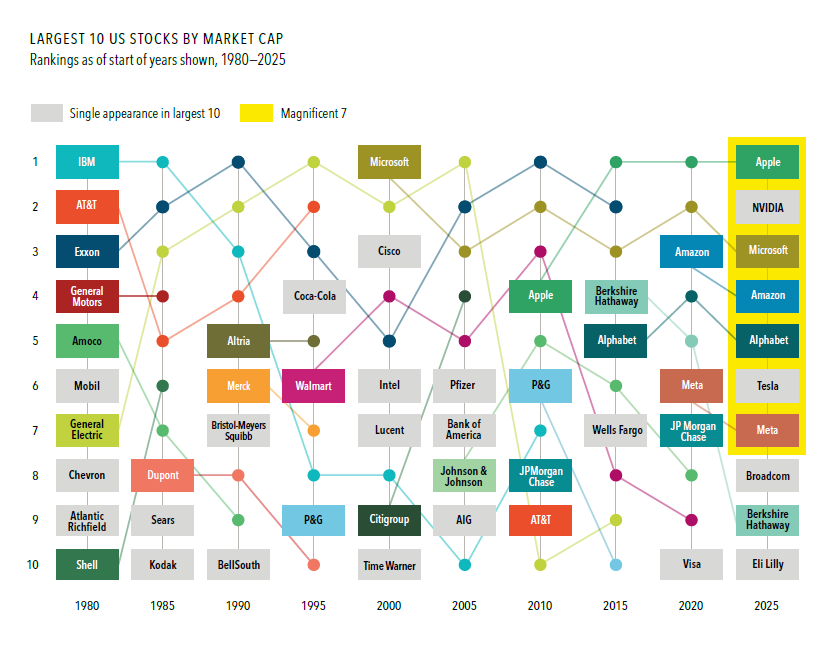

Why settle for less than one percent of what was owed? The Rule of 72 provides part of the answer. At 7.2% returns, money doubles every 10 years. That $170 million settlement has grown to $1.66 billion in net assets today - nearly a tenfold increase in 27 years.[6] But it required stopping the fight and starting to invest.

The opportunity cost of delay is staggering. Every year spent fighting is a year money isn't compounding. Every year locked in grievance mode is a year not building for the future. The settlement allowed Ngāi Tahu to shift from survival mode to growth mode, from defending what was left to creating what could be.

This principle extends far beyond Treaty settlements:

Family disputes over estates burn tens of thousands in legal fees while the assets stagnate or depreciate.

Former business partners spend more on lawyers than the company was ever worth.

Divorce battles consume resources that could be rebuilding two separate lives.

We hang in there because the principle matters, we deserve more, and because justice demands it.

And principle does matter. Justice is real – but so is your future. So is your peace of mind. So is the life you could be building instead of the grievance you're nursing.

Sometimes the juice isn't worth the squeeze.

The Value in Moving Forward

Holding grievances costs your mental health, your wellbeing, your ability to move forward – not to mention the fiscal cost. The human mind has limited bandwidth. Energy spent on past wrongs is energy unavailable for future opportunities. Anger may be righteous, but it's still corrosive.

You can be right, and still be trapped in a bad situation.

The settlement let Ngāi Tahu stop fighting the past (justified though they were) and start creating the future. That psychological shift may be worth more than any dollar figure – but the dollars did add up as well. Within a generation, the iwi went from near-extinction to becoming one of New Zealand's major economic and cultural forces. The asset base grew, yes, but so did everything else: language revitalisation programs, educational scholarships, marae restoration, cultural renaissance.

Modern New Zealand is a nation where nearly one in three people are first generation migrants, with fresh eyes unburdened by our nation’s history. These newcomers don't carry the weight of Te Hapa o Niu Tireni – the broken promises – and perhaps that lightness allows different possibilities.

That’s not to say we should forget. The name still hangs above Arowhenua Marae. The history is taught, remembered, and honoured. Moving on doesn't mean sweeping things under a rug and forgetting they existed. It means choosing where to invest your finite resources: backward into grievance, or forward into growth.

This Waitangi weekend, we celebrate a nation learning to move forward together, imperfectly but persistently. The dogskin cloak is long gone, but the lessons remain.

Sometimes "full and final" is the smartest decision you'll make. Not because you got everything you deserved, or because justice was fully served – but because opportunity cost exceeds what most people imagine.

In investment, and in life, the math is unforgiving. Every year looking backward is a year not compounding forward.

That's the real lesson Ngāi Tahu learned, twice over. Once the very hard way, fighting themselves while enemies approached, and once by choice: taking less than they deserved, and turning it into more than anyone expected.

The question isn't whether your grievance is justified. It probably is. The question must instead become: what's it costing you to hold on? And what could you build if you let it go?

Nick Stewart

(Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Huirapa, Ngāti Māmoe, Ngāti Waitaha)

Financial Adviser and CEO at Stewart Group

Stewart Group is a Hawke's Bay and Wellington based CEFEX & BCorp certified financial planning and advisory firm providing personal fiduciary services, Wealth Management, Risk Insurance & KiwiSaver scheme solutions.

The information provided, or any opinions expressed in this article, are of a general nature only and should not be construed or relied on as a recommendation to invest in a financial product or class of financial products. You should seek financial advice specific to your circumstances from a Financial Adviser before making any financial decisions. A disclosure statement can be obtained free of charge by calling 0800 878 961 or visit our website, www.stewartgroup.co.nz

Article no. 443

References

[1] Mikaere, B. (1988). Te Maiharoa and the Promised Land. Auckland: Heinemann.

[2] Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. (n.d.). Claim History. Retrieved from https://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/ngai-tahu/creation-stories/the-settlement/claim-history/

[3] Arowhenua Marae. (n.d.). Te Hapa o Niu Tireni - The Broken Promises of New Zealand. Temuka, South Canterbury.

[4] Mikaere, B. (1988). Te Maiharoa and the Promised Land. Auckland: Heinemann.

[5] Solomon, M. with Revington, M. (2021). Mana Whakatipu: Ngāi Tahu Leader Mark Solomon on Leadership and Life. Massey University Press.

[6] Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. (2024). Annual Report 2024. Retrieved from https://ngaitahu.iwi.nz